At the start of 2002, prospects were bright for Hawai’i’s kava (‘awa) producers. During the previous decade, the consumer base for kava had expanded beyond drinkers of the traditional water-based kava beverage to include the much larger nutritional supplement market. Kava capsules were prescribed in Europe to treat anxiety and insomnia.

At the start of 2002, prospects were bright for Hawai’i’s kava (‘awa) producers. During the previous decade, the consumer base for kava had expanded beyond drinkers of the traditional water-based kava beverage to include the much larger nutritional supplement market. Kava capsules were prescribed in Europe to treat anxiety and insomnia.

By year’s end, the kava industry had collapsed. At least 68 suspected cases of kava-linked liver toxicity had been reported, including nine liver failures that resulted in six liver transplants and three deaths. Countries in Europe, Asia, and North America had banned the sale of all kava products. In the U.S., where the Federal Drug Administration issued warnings but did not institute a ban, supplement sales plummeted.

Kava growers, users, and researchers were perplexed. Pacific Islanders have used kava for at least two thousand years without liver damage.

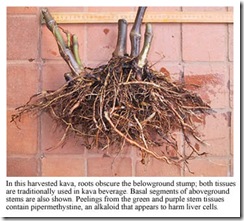

Kava (Piper methysticum G. Forster) is a shrub that belongs to the same botanical family as black pepper. It is cultivated throughout the Pacific Islands, where its roots and underground stump tissues are pulverized and extracted with water to make a tongue-numbing, earth-flavored beverage that is consumed in ceremonies and at social functions. The water-based kava drink contains kavalactones, pharmacologically active compounds that relax muscles, ease nervous tension, and promote sleep. Outside the Pacific Islands, kava users typically consume the plant in capsules or tablets. Pharmaceutical companies extract the root powder with solvents to enrich the kavalactone content of these products and for standardization purposes.

Prof. Tang began research on kava liver damage in July 1999. He focused on questions of toxicity after the kava market crashed. A Fijian trader told him that in 2000 and 2001, a period during which the supply of kava roots was insufficient to meet demand, European pharmaceutical companies had purchased kava stem peelings (bark), considered a waste product by traditional kava users. This practice may have been widespread. By 1998, the first year in which reports proposed a link between kava and liver toxicity in German and Swiss supplement consumers, dried bark constituted 82% of U.S. kava imports. This bark probably included stem peelings in addition to stump tissues.

Stem peelings are rich in kavalactones, but contain other compounds as well. Twenty years before issues of kava toxicity emerged, kava stems and leaves were reported to contain the alkaloid pipermethystine. While investigating the chemicals present in leaves and peelings from the aboveground stem, Tang and Dragull discovered a problem with the analytical method commonly used on kava. The high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) assay for kavalactone concentration was unable to distinguish between pipermethystine and a kavalactone, yangonin. So, if stem peelings were extracted and concentrated to generate kava capsules, pharmaceutical companies relying on HPLC could confuse the contaminant pipermethystine for the desirable product yangonin.

Liver cell studies conducted by Prof. Pratibha Nerurkar (MBBE) suggest that alkaloid contamination may play a key role in the liver toxicity associated with kava. Pipermethystine has a strong negative effect on liver cell cultures. Kavalactones, on the other hand, have not been found to damage cultured liver cells. Profs. Tang and Nerurkar plan to investigate these toxicity issues further using rats as an animal model.

Prof. Tang and Mr. Dragull determined that gas chromatography is able to distinguish yangonin from pipermethystine, and confirmed the presence of pipermethystine in stem peelings. In addition, they and Mr. Yoshida purified and characterized two previously unknown kava alkaloids. Awaine, named after the Hawaiian word for kava, was found in varying concentrations in the unopened leaves of all eleven cultivars tested. An epoxy alkaloid similar to pipermethystine was present in stem peelings and leaves of the Isa cultivar. The ability of pipermethystine to form a relatively stable epoxide may be associated with its apparent toxicity to liver cells.

The UH researchers did not detect the three dangerous alkaloids in commercial kava root powders, and Prof. Tang believes that the traditional kava beverage is not harmful. (Kona Kava Farm has always used only roots for all of our Kava products, and part of the reason why, is exactly what this study shows.) The study recommends that consumers avoid kava products that may contain aerial tissues, including capsules, tablets, and kava leaf tea. Prof. Tang hopes that these research findings will help resuscitate the industry by leading to the repeal of national bans on products made from only kava roots and stumps.

No Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks